The recent ransomware attack on Toll Group underscores the susceptibility of Australia’s transport and logistics sector to cybercrime

It started with an inconspicuous message on Toll’s website about a precautionary shut-down of its IT systems and unfolded into one of the highest-profile cyberattacks in transport and logistics history – let alone the corporate world.

It’s brought into sharp relief the vulnerability of an industry ever-reliant on technology to fall victim to cybercrime, especially if a corporate giant with vast resources such as Toll is susceptible.

Though it’s still early days in the aftermath, the attack may have a lasting technological and financial impact on Australia’s T&L sector.

TIMELINE

The warning message appeared on a Friday, January 31, soon after “unusual activity” was detected in some of Toll’s IT systems, a company spokesperson tells ATN.

“Based on our early assessment, we moved quickly to disable our servers in order to contain the risk,” they explain.

After further risk assessment revealed the extent of the incident, the company moved into crisis management mode, disabling its IT network.

“That included shutting down some 500 applications that support all of our operations and deploying our business continuity plan, which included a combination of manual and automated processes to maintain operations and services.”

The original message flew under the radar over the weekend, but then came the social media grumblings from customers, and speculation from media and IT analysts.

Toll had to act fast – not just behind the scenes, but publicly.

On one hand, it was dealing with a ransomware attack, consulting with authorities including the Australian government’s lead cybersecurity agency, the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), on a recovery. On the other, it still had a business to run, meaning reassuring customers – and the public – on the functionality of its operations.

“We have detailed business continuity plans designed for a range of major incidents and scenarios, including cyberattacks of the kind we experienced,” the spokesperson says.

“While every situation is different, our business continuity processes were instrumental in ensuring we were able to keep things moving as we swung into action over the ensuing days and weeks to progressively and securely reactivate systems.

“The nature of large-scale cyberattacks calls for a balance between how much information is disclosed publicly without compromising investigations into what is a serious criminal activity.

“While mindful of this, open and timely communication is important and we moved quickly to instigate our crisis communication processes to ensure we were able to keep our customers, employees and the broader market informed.”

How news broke of the Toll cybersecurity incident, here

Toll did, within a few days, disclose that it was the victim of a ‘Mailto’ ransomware attack, which hits Windows systems.

The company did not pay the ransom – experts advise victims not to, as there’s no guarantee the perpetrators will cooperate – and did not suspect any personal data was breached.

In the meantime, staffing increased at contact centres to assist with customer service while global cyber security experts helped find a fix and criminal investigations were underway.

“For MyToll customers who transact with us online, we boosted resources for our call centres and provided regular updates via the MyToll website including FAQs and the like,” the spokesperson says.

“For our enterprise-level customers, it’s been a targeted and tailored process to address their specific needs.”

Eventually, throughout February, services across the global network started to return to full service – though were not completely restored at the time of writing.

Reviews of the affected IT hardware – including servers, systems and devices – continued to ensure any risk associated with the incident was appropriately managed and neutralised.

“We’ve made good progress in reactivating many of our systems and we’re well-placed to resume normal operations across the entire global network,” the spokesperson says.

“At the same time, there are some customers where more complex reintegration of systems is required and we’re working closely with them to make that happen as soon as possible.”

Most updates came with an apology for the ongoing inconvenience, and a thanks for patience and understanding.

Many sympathised with the situation but other consumers weren’t as amiable.

HOW MALWARE WORKS

Cybercrime operations are relentless, with the personal and corporate toll continuing to mount.

Last year, IT security company Mimecast observed a coordinated campaign targeting T&L operators between October 22-25, using masses of Emotet, a malware strain that started as a Trojan aimed at stealing banking credentials, identified as a major threat here by the ACSC on October 24, 2019. More than 8,000 detections were made.

Mimecast Australia principal technical consultant Garrett O’Hara, pictured, tells ATN such cyber operations are always evolving but can be traced back to existing code bases.

They can involve malicious links, weaponised attachments, credit harvesting or even ‘social engineering’ – more on that later.

The scariest prospect is there often aren’t any warning signs.

“Attackers can often be lurking in the background of an organisation for months – known as dwell time – traversing networks, jumping around and trying to get themselves embedded as much as possible.”

In fact, IT giant IBM’s 2019 Cost of a Data Breach report places the average time to identify and contain a breach at 279 days, and the full lifecycle of a malicious attack from breach to containment at 314 days.

WHY T&L?

Craig McDonald, founder of web and email security company Mailguard, notes logistics is a favourite among cybercriminals for three key reasons.

“Firstly, companies typically have a wide network of third-party relationships – making them a gold mine of data,” he writes in a blog.

“Secondly, companies like Toll Group have a large and complex supply chain ecosystem that relies heavily on cyber-based control, navigation, tracking, positioning and communications systems … [with] multiple digital vulnerabilities that make it easier for cybercriminals to infiltrate their networks.

“Third, the nature of their business is time critical, so they are under more pressure to make a call on paying the ransom so as to not disrupt their operations, and the businesses of all of those that are depending on their deliveries.”

SAFEGUARDING

While defence systems are ever-improving, and today automated systems can detect a breach, contain it and disable an infected system “at a speed a human is incapable of”, user education should still be at the fore, O’Hara says.

Ultimately, all it takes is an unpatched Windows system and one click of a malevolent link.

“We’ve started to think about malware in zones, with zone one being what was traditionally the perimeter – that’s going to protect against your basic viruses, things like malicious links and attachments.

“Then there’s zone two, which relates to the inside of the organisation. Users will have access to their Gmail accounts, where they can log on and bring down links and attachments, which can bypass your corporate email security.

“That’s where you need to educate the users so they know the right thing to do; they won’t click on links, they won’t open attachments, all the things you hope that they’re smart enough to do.”

There’s an emergence of attacks where the attacker registers a domain that, to an employee, will look like their firm’s.

“What they’re trying to do is convince the end user that they’re seeing something that’s from their corporate domain, or maybe a domain that is a vendor organisation or a partner organisation for a logistics company,” O’Hara says.

“There’s a trust and a social engineering thing that happens there.

“So, zone three is about companies looking outside of the organisation to analyse the infinite web for domains that they don’t own.

“Through scanning and using technologies like machine learning, we can understand if there are sites out there that look similar to the organisation’s domains in a suspicious way – you can automatically take that domain down.”

Finally, O’Hara says it’s imperative that transport operators ensure their data is backed up and secure.

“This is so that, for example, you still know where in the world a particular shipping container is, or a package is about to arrive at somebody’s house; that critical data, which, if lost, would leave you in a fair amount of trouble.

“Emails are an important part of that too. Having secondary copies of that data in a secure place is very important.”

COMMUNICATION CRITICAL

If an incident does occur, there’s no point trying to sweep it under the carpet, O’Hara contends. It’s accepted that cyberattacks occur and companies are better off being upfront to customers and the public.

“A mistake that some organisations have made is to shut down communications, and what often happens then is that people kind of assume the worst and you’ll see social media going wild with speculation,” he says.

“You need to respond in terms of being able to deal with the media and manage the conversation to customers so that they’re aware of the status.

“Controlling the narrative post breach is very important. Even if the news is that there is no news other than there’s an ongoing investigation, having that open communication is still important so people know the organisation is taking action.”

Though some may not agree, McDonald backs Toll’s communications approach to the incident.

“While a few media outlets have criticised them for not being more forthcoming about the attack, the transparency of their response is reassuring.

“Many businesses today still prefer to remain tight-lipped when their company experiences a cyberattack.

“By contrast, Toll Group [provided] regular updates about what has happened and the measures that are being undertaken to protect their customers.”

COUNTING THE COST

Cybercrime can be a lucrative business for the perpetrators and crippling for the victim and associated parties.

Cost of a Data Breach estimates the average cost of a data breach is A$5.52 million per firm, and the ripple effect costs third parties $560,000.

At the higher end, American courier giant FedEx reported 2017’s ‘NotPetya’ malware attack on Dutch subsidiary TNT had “an estimated US$300 million (A$374 million) impact”; Danish logistics conglomerate Maersk suffered a near-identical hit.

Toll hasn’t yet put a figure on the attack but public records show it comes at an inopportune time.

Parent Japan Post’s results for the nine months up to December 31, 2019 reveal a $78 million loss, “owing to deterioration of external environment including a slowing Australian economy and US-China trade friction”, and that’s before counting the cost of the Australian bushfire season, Covid-19 and the Mailto attack.

“These are complex issues and we don’t hide from the fact that not everything’s working perfectly. We’ve made good progress in isolating the problem and we’re working to gradually reinstate systems securely,” Toll’s managing director Thomas Knudsen, pictured, noted on social media at the time.

“While Toll Group’s recent cyberattack has presented significant challenges, as incidents of this scale will do, we mobilised quickly and decisively to firstly contain the risk and then to focus on supporting our customers.”

Industry commentary from Freight and Trade Alliance (FTA) director Paul Zalai notes the industry still feels “widespread downstream problems” from Maersk’s 2017 attack, but “most firms” have not made their systems more resilient.

“For whatever reason [Toll] got cracked, but I think they were the unlucky ones and there would be many others just as vulnerable,’’ he says in a communique.

“The bigger thing this has exposed is the risk to other logistics providers as well … We are well aware that many are hosting their own servers and their own technology, they run with myriad different systems and are trying to piece them all together.

“The more complex these systems architecture are, then the greater the risk is for cyberattack.”

Zalai cites “rampant merger and activity and numerous firms making a false economy of running old tech systems into the ground [meaning] well organised cyber criminals could easily run wild”.

At the time, Toll was undergoing its “largest ever” IT rationalisation effort led by CIO Françoise Russo.

“We’re well down the path of a three-year IT transformation program which puts us in a much better position than we might’ve been a few years ago to deal with a situation like this,” Toll’s spokesperson says.

LESSONS LEARNED

Toll’s spokesperson sums up the situation by admitting: “Incidents of the scale and complexity that we’ve experienced test every aspect of your business and, in that sense, there are always learnings.

“We’ve come to realise the value of robust business continuity plans and processes – ours stood up well in terms of being able to keep things moving for our customers, albeit with the inevitable challenges that come when services are disrupted.

“Another is making sure you have the right people to supplement the in-house team, from cyber security experts to agencies like the ACSC.”

Toll also admits it learnt the value of communicating and often throughout the incident.

“That means being ready to deploy a range of channels online and offline, including alternative platforms where the conventional options are unavailable.

“It was also about making sure the information was relevant to the needs and circumstances of different customer groups.”

WHAT IS MAILTO?

In the wake of the Toll attack, ACSC added ‘Mailto/Kazakavkovkiz’ to its directory of cyber threats, part of the ‘KoKo’ ransomware family that encrypts victims’ files to demand ransom in exchange for a decryption key.

It is distributed by hacking through means such as email spam, malicious attachments, fake updates, and infected installers.

Once inside the system, Mailto will target commonly used files (such as .pdf, .zip, .doc, .mp4). Once encrypted, a file is renamed and is no longer accessible.

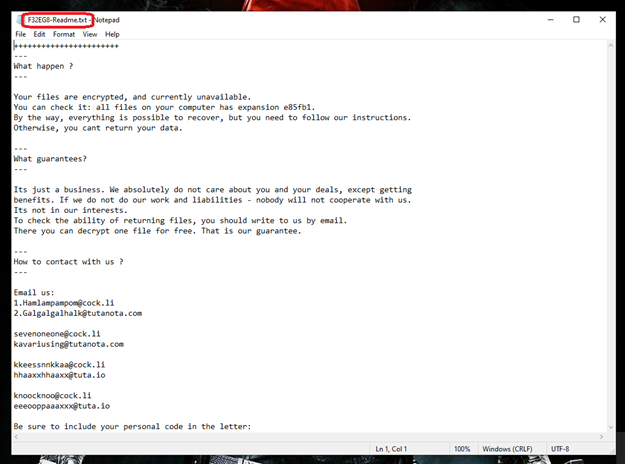

Users may see ransom note (pictured) that claims data recovery is not possible unless they contact a designated email.

Cybercriminals will demand a ransom via a digital currency like Bitcoin to recover the key to locked files.