Suicide by truck isn’t painless as the impacts go beyond the crashes. Toll’s road safety head is raising the issue in industry forums and talks about why

The year began with a very willing debate between the trucking industry and authorities about the latter’s approach to dealing with truck-related fatalities.

Sparked by some high-profile New South Wales tragedies and a fatality spike in that state, what later became obvious was a lack of clarity surrounding how this horror is measured and where the responsibility lies.

It is a given that research on the industry generally is ad hoc and haphazard, and that the industry feels scapegoated for an issue where even the varying statistics show that accidents are out of its control most of the time.

The Australian Trucking Association (ATA) is just the most recent player to call for a stronger statistical focus on the industry to provide a trusted and agreed upon statistical basis to underpin informed decision-making.

HARD QUESTIONS

Into this unsettled scene steps Toll Group general manager road transport safety and compliance Dr Sarah Jones with questions that have implications for this debate, as well as wider ones for fleet operations: What can we do about the phenomenon of ‘suicide by truck’ (SBT)? And what impact is this having on our drivers?

The issue crystallised for Jones as she sought to get a grip on the facts about fatalities involving Toll trucks.

“In order to prevent on-road fatalities we need to understand why they occur,” she tells ATN.

“Through looking for patterns, characteristics, trends and anomalies in the data we can target intervention more precisely.

“We were surprised by the incidence of suicide by truck in our data.

“This exercise highlights the value of taking a fresh look at data and the risks that might be hidden there.”

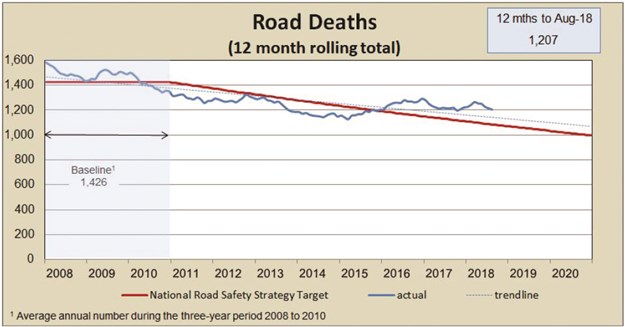

The company desires to resist the national road toll trend, which has been going the wrong way recently, hence the spur for the report.

But suicide is a fraught subject in general society and the focus naturally is on proactively treating those who might seek it.

It is as prevalent in transport and logistics as much as any other industry.

As well as the aftermath that company owners, managers and drivers do their best to cope with, SBT is also an aspect of the statistical debate. But just how it might be handled is unclear.

“Confirmed suicides are removed from the official road toll,” Jones says.

“However, it is often quite difficult to make a determination of suicide because of the question of intent.

“Suicide by truck may be chosen precisely because it can look like an ‘accident’.”

She touches on the last year’s “Suicide and murder-suicide involving automobiles” article in Australian Psychiatry, which notes that “with vehicles available, driver suicide may be chosen for the sake of family and friends”.

BARELY AN EXPERT WHISPER

And this is where the statistical near-silence comes to the fore – ATN has been unable to find an academic study focused solely on SBT, though it has been mentioned in wider accident studies and a group of researchers in the US have sought funding to undertake one.

So trying to get a handle on what proportion of fatal crashes involves SBT is particularly difficult.

One of the few studies to estimate it – Accident analysis for traffic aspects of high capacity transports – comes from Sweden’s Chalmers University of Technology in 2014.

Based on crash investigations, researchers there estimate that SBT accounted for 17.2 per cent of large truck crashes in Europe and North America, while for 8.7 per cent the cause was “unknown”.

“The in-depth study of the 379 fatal crashes involving [heavy goods vehicles] included 65 crashes classified as suicides, all of which were head-on collisions,” the study states.

“These crashes were considered to have been caused by conscious human intervention.”

Along with the Australian Psychiatry report, probably the most relevant Australian effort is from the Monash University Accident Research Centre (MUARC).

It estimated that driver suicide accounts for between 1.1–7.4 per cent of all traffic fatalities.

That study was completed in 2003 and a MUARC spokesperson says there are no plans at present to update it.

A Finnish report from 1997 put the general rate in that country at 5.9 per cent of all fatal crashes.

There are many variables at work in collating such figures, including whether or not a note is left.

Though some psychiatric health professionals rely heavily on notes as a signpost, there are weaknesses.

The US researchers mentioned above state: “An intentional traffic crash may be seen by desperate individuals as a quick, convenient and undiscoverable method. It avoids insurance complications and religious disapprobation. Suicide via a traffic crash is especially suited for alcohol-impaired, spur-of-the-moment death impulses.”

WHAT TOLL FOUND

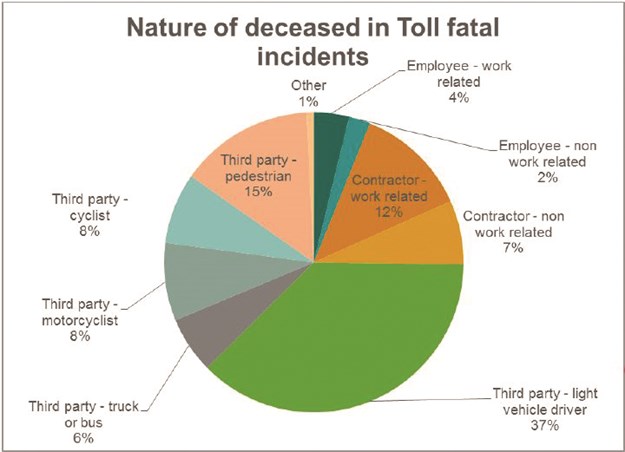

Jones’ fatalities study covered Toll employees, contractors and casuals.

She has made a related presentation, Suicide by Truck – the Toll experience, to the Steering Committee of the National Road Safety Partnership Program.

The conclusion was 14 per cent of incidents are confirmed suicide by truck and that this is “almost certainly an underestimate”.

This is because Coroner’s courts have a presumption against suicide and the recognised tendency for some souls to disguise the cause.

Toll’s estimate is that the total is “closer to 20 per cent”, though this is within a range of 14–20 per cent.

As a backdrop, Toll’s total global annual involvement in on-road fatalities and driver deaths in Toll premises and vehicles in 2007/08 were 16; in 2015/16, the last full year of data comprehensively analysed, there were 12.

PAST THE WERTHER EFFECT

A central reason suicide debate is so fraught is the Werther effect – the risk that sharing information about suicide inadvertently leads to more such deaths.

It tends to make a difficult task harder, but avoiding the subject is almost as bad as it discounts the wider effects and leaves the impact on the living unacknowledged.

Dr Jones, is sure progress can and must be made.

“The first step is acknowledging that there is an issue,” she says.

“Policy resources tend to be directed to areas of highest risk, but the data on suicide by truck is largely invisible [or] hidden so it has not attracted attention.

“We need to be candid with truck drivers that suicide by truck is an occupational hazard and be up-front about the psychological impact this experience can have.

“A driver who is informed about the risk of trauma-induced depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress can recognise symptoms at an early stage.

“Fortunately there is an increasing awareness of the role mental health plays in safe and productive workplaces, so hopefully the stigma around seeking help/acknowledging the impact is reducing.

“The National Road Safety Partnership Program has created a working group to consider how we can tackle the issue. I attended the initial workshop and it was very positive. Coroners, mental health professionals, road safety experts and government road agencies were all in the room contributing their perspective.

“Thirdly, we need to commit to talking about suicide by truck in a responsible, sensitive way. Language is important.

We need to recognise the risk of copy-cat events and emphasise that help is available when we talk about the issue.”

DEALING WITH WHAT COMES AFTER

Anecdotal evidence is that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one significant outcomes of SBT.

Others include shame and depression and sleeplessness.

The ripple effects can include financial pressures on truck drivers’ families if the drivers seek a recovery break or if they leave the industry altogether, and this is true of PTSD from any source.

Toll classifies all fatalities as significant safety incidents, or SSIs.

“They require thorough investigation. All drivers involved in fatalities or other serious incidents are required to debrief and are offered counselling and assistance, either through the Toll Chaplaincy or the Employee Assistance Program,” Toll Group general manager for road transport safety and compliance Dr Sarah Jones says.

Toll’s group manager of wellbeing and senior chaplain is Ruth Oakden.

“While not all people affected following an incident go on to receive a formal diagnosis of PTSD, the signs associated with this condition and the symptoms experienced by the employees – and often their families – would imply this is the case,” she tells ATN.

“Intrusive memories, flashbacks, situational avoidance, sleeplessness, irritability, mood changes, sense of self blame and other conditions associated with PTSD are all described in discussion with drivers (families) and other affected employees.

“Early and effective intervention appears to reduce the impact of these symptoms and provides the opportunity to return to ‘normal’ or acceptance of the event.”

Toll’s approach to rehabilitation and recovery comes into play for SBT incidents as it would other trauma.

“Generally speaking, unless prevented by injury (physical or emotional), we aim to have the affected employees return to normal duties as quickly as possible,” Oakden says.

“This is primarily to allow the affected employees the opportunity to resume their ‘normal’ work and lifestyle.”

She gives the following outline:

• Early access to internal counselling, employee support and external employee assistance programs promotes recovery and assists engagement with emotional rehabilitation

• We discuss strategies to avoid unnecessary re-telling of the event in order to reduce the re-lived experience

• We provide the opportunity for flexible and staged return to work

• Supported drive-by of incident site, e.g.

– Passenger in the car

– Driver with support

– Passenger in truck

– Driver in truck with support

– Short trip with support available at beginning and conclusion

Support may be a peer, supervisor, HSE rep, friend or mental health professional

• Follow up at key points, particularly for drivers who are “fine” and don’t take up initial support options.

“We are in the process of introducing a pre-emptive program (from the TrackSafe model) as a component of our driver education that recognises the risks associated with road incident fatalities/ suicides/ major incidents and provides an open forum to discuss how these incidents may affect people if they occur, and provides details of the support process that is available in the event of an incident,” Oakden explains.

“This will blend with our post incident support program with the intention that the combination of training will equip those affected with the skill set and understanding of resources to help support them through the crisis.

“These programs are aligned with our mental health programs, which aim to raise awareness for individuals and throughout the culture of the workplace to increase understanding of mental health issues and provide the language to discuss issues, as well as opportunities for care and support.

“Our rehabilitation/recovery/return to work approach is a framework. We are mindful that people respond very differently to stressful situations. Some say they are ‘fine’ some really are fine.

“We need to provide long- and short-term responses and allow for recovery that may not be longitudinal or consistent.

“A key resource is the input of aware colleagues and supervisors during the recovery and return to work.”

This approach chimes with views in the US.

American Foundation for Suicide Prevention vice president of research, Dr Jill Harkavy-Friedman, tells US magazine Fleetowner: “It’s important for fleets to check in with the driver, assure him that his job is not jeopardized… managers should be on the lookout for stress disorders and substance abuse.

“Drivers may think they’re fine at first but it can affect them later.”

She too identifies a lack of regular responses from drivers.

“It is difficult to compare individuals’ responses to different types of trauma and evidence is not available to compare truckers involved in suicide versus accidental death. Personal and situational factors play key roles in response to trauma,” she says.

If you have been affected by this article, help can be found at Lifeline on 13 11 14, and beyondblue on 1300 22 4636.